Notes & Resources

The following excerpts are from relevant notes compiled in my research.

Art as Experience by John Dewey

Relevant notes:

We are, as it were, introduced into a world beyond this world, which is nevertheless the deeper reality of the world in which we live in our ordinary experiences. We are carried out beyond ourselves to find ourselves. P202

We cannot answer these questions any more than we can trace the development of art out of everyday experience, unless we have a clear and coherent idea of what is meant when we say “normal experience.”

"The first great consideration is that life goes on in an environment; not merely in it but because of it, through interaction with it." P12

To the being fully alive, the future is not ominous but a promise; it surrounds the present as a halo. It consists of possibilities that are felt as a possession of what is now and here.

Art celebrates with peculiar intensity the moments in which the past reinforces the present, and in which the future is a quickening of what is now is. P 17

The past is carried into the present so as to expand and deepen the content of the latter.

In other words, art is not nature, but is nature transformed by entering into new relationships where it evokes a new emotional response. P82

Works of art that are not remote from common life, that are widely enjoyed in a community, are signs of a unified collective life.

The remaking of the material of experience in the act of expression is not an isolated event confined to the artist and to a person here and there who happens to enjoy the work. It is also a remaking of the experience of the community in the direction of greater order and unity. P84

The work of art is complete only as it works in the experience of others than the one who created. P110

Works of art, like words, are literally pregnant with meaning. Meanings, having their source in past experience, are means by which the particular organization that marks a given picture is effected.

The material out of which a work of art is composed belongs to the common world rather than to the self, and yet there is self- expression in art because the self assimilates that material in a distinctive way to reissue it into the public world in a form that builds a new object. P112

It is significant that the word "design" has a double meaning. It signifies purpose and it signifies arrangement, mode of composition. ...ordered relations of elements. P121

But whatever path the work of art pursues, it, just because it is a full and intense experience, keeps alive the the power to experience the common world in its fullness. It does so by reducing the raw materials of that experience to matter ordered through form. P138

Only because an artist operates experimentally does he open new fields of experience and disclose new aspects and qualities in familiar scenes and objects.

But any experience the most ordinary, has an indefinite total setting. Things, objects, are only focal points of a here and now in a whole that stretches out indefinitely.

Coleridge said that every work of art must have about it something not understood to obtain its full effect.

Dewey, J. (2005). Art as experience. New York, NY: Perigee

Relevant notes:

We are, as it were, introduced into a world beyond this world, which is nevertheless the deeper reality of the world in which we live in our ordinary experiences. We are carried out beyond ourselves to find ourselves. P202

We cannot answer these questions any more than we can trace the development of art out of everyday experience, unless we have a clear and coherent idea of what is meant when we say “normal experience.”

"The first great consideration is that life goes on in an environment; not merely in it but because of it, through interaction with it." P12

To the being fully alive, the future is not ominous but a promise; it surrounds the present as a halo. It consists of possibilities that are felt as a possession of what is now and here.

Art celebrates with peculiar intensity the moments in which the past reinforces the present, and in which the future is a quickening of what is now is. P 17

The past is carried into the present so as to expand and deepen the content of the latter.

In other words, art is not nature, but is nature transformed by entering into new relationships where it evokes a new emotional response. P82

Works of art that are not remote from common life, that are widely enjoyed in a community, are signs of a unified collective life.

The remaking of the material of experience in the act of expression is not an isolated event confined to the artist and to a person here and there who happens to enjoy the work. It is also a remaking of the experience of the community in the direction of greater order and unity. P84

The work of art is complete only as it works in the experience of others than the one who created. P110

Works of art, like words, are literally pregnant with meaning. Meanings, having their source in past experience, are means by which the particular organization that marks a given picture is effected.

The material out of which a work of art is composed belongs to the common world rather than to the self, and yet there is self- expression in art because the self assimilates that material in a distinctive way to reissue it into the public world in a form that builds a new object. P112

It is significant that the word "design" has a double meaning. It signifies purpose and it signifies arrangement, mode of composition. ...ordered relations of elements. P121

But whatever path the work of art pursues, it, just because it is a full and intense experience, keeps alive the the power to experience the common world in its fullness. It does so by reducing the raw materials of that experience to matter ordered through form. P138

Only because an artist operates experimentally does he open new fields of experience and disclose new aspects and qualities in familiar scenes and objects.

But any experience the most ordinary, has an indefinite total setting. Things, objects, are only focal points of a here and now in a whole that stretches out indefinitely.

Coleridge said that every work of art must have about it something not understood to obtain its full effect.

Dewey, J. (2005). Art as experience. New York, NY: Perigee

The Riddle of Experience vs Memory by Daniel Kahneman

click here for Ted Talk Video

click here for Ted Talk Video

|

Full transcript of Ted Talk:

|

| ||||||

Notes from The Riddle of Experience vs Memory transcript:

The second trap is a confusion between experience and memory; basically, it's between being happy in your life, and being happy about your life or happy with your life.

What this is telling us, really, is that we might be thinking of ourselves and of other people in terms of two selves. There is an experiencing self, who lives in the present and knows the present, is capable of re-living the past, but basically it has only the present.

And then there is a remembering self, and the remembering self is the one that

keeps score, and maintains the story of our life, and it's the one that the doctor approaches in

asking the question, "How have you been feeling lately?" or "How was your trip to Albania?" or

something like that.

Now, the remembering self is a storyteller. And that really starts with a basic response of our

memories -- it starts immediately. We don't only tell stories when we set out to tell stories. Our

memory tells us stories, that is, what we get to keep from our experiences is a story.

What defines a story? And that is true of the stories that memory delivers for us, and it's also true of the stories that we make up. What defines a story are changes, significant moments and endings.

It has moments of experience, one after the other. And you can ask: What happens to these moments? And the answer is really straightforward: They are lost forever.

Most of them are completely ignored by the remembering self. And yet, somehow you get the sense that they should count, that what happens during these moments of experience is our life. It's the finite resource that we're spending while we're on this earth. And how to spend it would seem to be relevant, but that is not the story that the remembering self keeps for us.

So we have the remembering self and the experiencing self, and they're really quite distinct. The

biggest difference between them is in the handling of time.

We actually don't choose between experiences, we choose

between memories of experiences. And even when we think about the future, we don't think of

our future normally as experiences. We think of our future as anticipated memories.

Why do we put so much weight on memory relative to the weight that we put on experiences?

So I want you to think about a thought experiment. Imagine that for your next vacation, you

know that at the end of the vacation all your pictures will be destroyed, and you'll get an amnesic drug so that you won't remember anything. Now, would you choose the same vacation?

The second trap is a confusion between experience and memory; basically, it's between being happy in your life, and being happy about your life or happy with your life.

What this is telling us, really, is that we might be thinking of ourselves and of other people in terms of two selves. There is an experiencing self, who lives in the present and knows the present, is capable of re-living the past, but basically it has only the present.

And then there is a remembering self, and the remembering self is the one that

keeps score, and maintains the story of our life, and it's the one that the doctor approaches in

asking the question, "How have you been feeling lately?" or "How was your trip to Albania?" or

something like that.

Now, the remembering self is a storyteller. And that really starts with a basic response of our

memories -- it starts immediately. We don't only tell stories when we set out to tell stories. Our

memory tells us stories, that is, what we get to keep from our experiences is a story.

What defines a story? And that is true of the stories that memory delivers for us, and it's also true of the stories that we make up. What defines a story are changes, significant moments and endings.

It has moments of experience, one after the other. And you can ask: What happens to these moments? And the answer is really straightforward: They are lost forever.

Most of them are completely ignored by the remembering self. And yet, somehow you get the sense that they should count, that what happens during these moments of experience is our life. It's the finite resource that we're spending while we're on this earth. And how to spend it would seem to be relevant, but that is not the story that the remembering self keeps for us.

So we have the remembering self and the experiencing self, and they're really quite distinct. The

biggest difference between them is in the handling of time.

We actually don't choose between experiences, we choose

between memories of experiences. And even when we think about the future, we don't think of

our future normally as experiences. We think of our future as anticipated memories.

Why do we put so much weight on memory relative to the weight that we put on experiences?

So I want you to think about a thought experiment. Imagine that for your next vacation, you

know that at the end of the vacation all your pictures will be destroyed, and you'll get an amnesic drug so that you won't remember anything. Now, would you choose the same vacation?

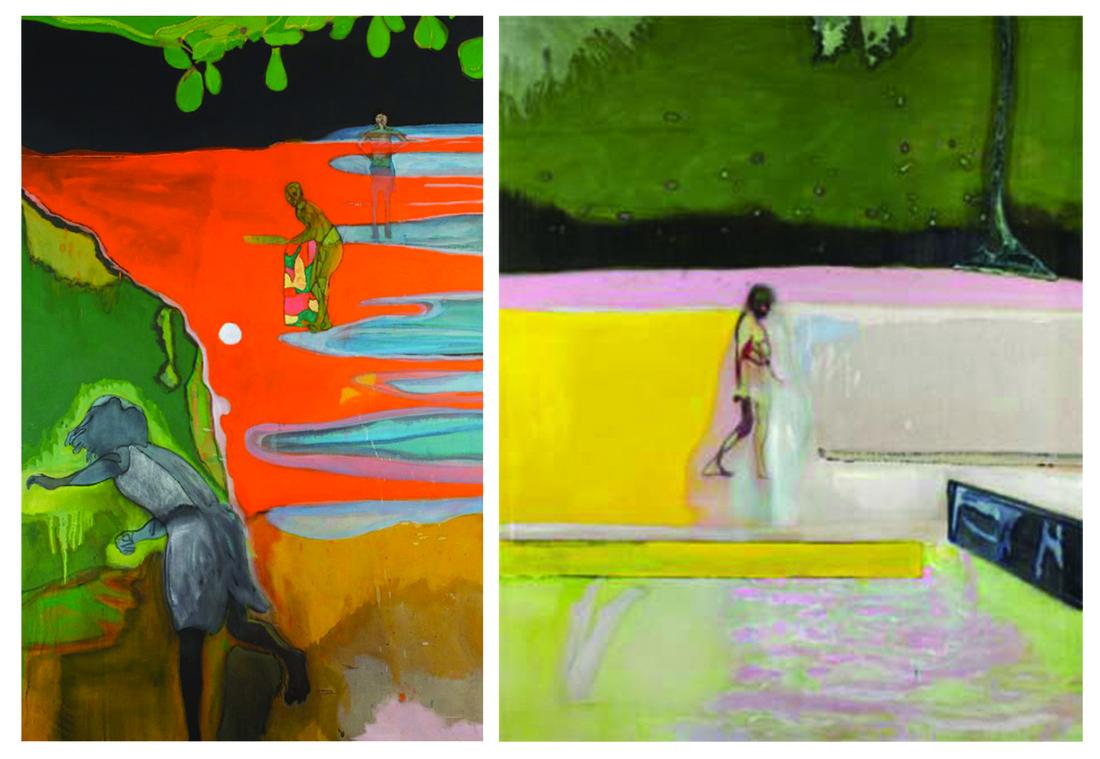

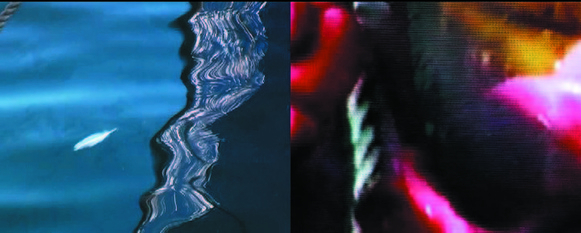

Slip Frame by Anne Robinson

Hold, twin screen video installation

Hold, twin screen video installation

Notes from the exhibit catalog, Slip Frame:

The elements that constitute the sequence-image, mainly perceptions and recollections, emerge successively but not teleologically, the order in which they appear is insignificant (as in a rebus) and they present an configuration - ‘lexical, sporadic’ - that is more ‘object’ than narrative.

Robinson is interested in the way in which affect is stimulated through chance encounters with images, possibly dissociated from their original context.

By using this non-linear construction and employing an accumulation of what might in other situations have been inconsequential fragments Anne Robinson seems to have constructed what Victor Burgin calls a ‘sequence-image’, which is elaborated in The Remembered Film.

This accretion of images might be considered analogous to thought and memory; the kind of way of thinking that happens when one is wandering around one place but thinking of another.

Although the effect of this is to divide the work into clear episodes it is certainly not in any way to build a conventional narrative. Through the conceit of showing still and moving images next to each other, the piece develops a complex blurring of the relationships between several apparent binaries; these include that which is still and that which is moving, that which is exterior and that which is interior, that which is directly experienced and that which is vicarious, that which was then and that which is now, what might be read as abstraction and what as representation and what is conscious and what unconscious.

For a viewer this allows for a paradoxical combination of meditative with transitory.

The images are nearly all made from re-filming from TV screens using a digital camera. This procedure can result in various kinds of visual disruption: from apparent blur and discolouration to an apparent smearing or smudging. Anne Robinson considers that this process is almost like “seeing through other eyes”.

Indeed, the artist thinks of re-filming in terms of the impossible attempt to capture the space between frames..."and I have started to look at spaces between frames, with the blurring of

frame spaces in digital imaging and editing; and to develop languages of re-filming to ‘catch’ these frames; exploring this as a space of the imaginary."

In her essay ‘Lydia Bauman: the Poetic Image in the Field of the Uncanny’ Griselda Pollock offers the following definition of the imaginary space that a landscape painting might proffer:

More than topography, its painted representations have offered poetic means to imagine our place in the world. The paradox of landscape is that it is both what is other to the human subject: land, place, nature, and yet, it is also the space for projection, and can become therefore, a sublimated self-portrait.

The artist is interested in the quality of the removed distance which post memory allows and the ways in which memory can be understood as cultural as well as individual. This also gives a context for the layered effect of displacement and distance in the work created through using slides, TV screens and re-filming. The refilmed images are of already mediated images of place-a double distance.

The artist considers that the way in which the results of re-filming distorts and changes might be linked to what happens when she paints. Painting is created through applying layer upon layer onto a surface. The layering in these video stills is not a literal one, but it is another kind of layering has occurred through accumulated processes involved.

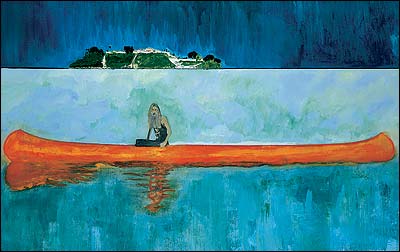

Since this sequence of projected images in Hold is so painterly they might be read in counterpoint to some contemporary painting, for example, the filmic, ethereal paintings of Peter Doig. He too privileges neither abstraction nor figuration. He too offers us composite places for projection that draw on as wide a range of source material as Anne Robinson. I am thinking, in this context, not only of the ambiguous almost dream-like sense of space he creates through the rich consistency of his densely worked surfaces, but in particular of his mix of autobiographical and filmic memories.

The elements that constitute the sequence-image, mainly perceptions and recollections, emerge successively but not teleologically, the order in which they appear is insignificant (as in a rebus) and they present an configuration - ‘lexical, sporadic’ - that is more ‘object’ than narrative.

Robinson is interested in the way in which affect is stimulated through chance encounters with images, possibly dissociated from their original context.

By using this non-linear construction and employing an accumulation of what might in other situations have been inconsequential fragments Anne Robinson seems to have constructed what Victor Burgin calls a ‘sequence-image’, which is elaborated in The Remembered Film.

This accretion of images might be considered analogous to thought and memory; the kind of way of thinking that happens when one is wandering around one place but thinking of another.

Although the effect of this is to divide the work into clear episodes it is certainly not in any way to build a conventional narrative. Through the conceit of showing still and moving images next to each other, the piece develops a complex blurring of the relationships between several apparent binaries; these include that which is still and that which is moving, that which is exterior and that which is interior, that which is directly experienced and that which is vicarious, that which was then and that which is now, what might be read as abstraction and what as representation and what is conscious and what unconscious.

For a viewer this allows for a paradoxical combination of meditative with transitory.

The images are nearly all made from re-filming from TV screens using a digital camera. This procedure can result in various kinds of visual disruption: from apparent blur and discolouration to an apparent smearing or smudging. Anne Robinson considers that this process is almost like “seeing through other eyes”.

Indeed, the artist thinks of re-filming in terms of the impossible attempt to capture the space between frames..."and I have started to look at spaces between frames, with the blurring of

frame spaces in digital imaging and editing; and to develop languages of re-filming to ‘catch’ these frames; exploring this as a space of the imaginary."

In her essay ‘Lydia Bauman: the Poetic Image in the Field of the Uncanny’ Griselda Pollock offers the following definition of the imaginary space that a landscape painting might proffer:

More than topography, its painted representations have offered poetic means to imagine our place in the world. The paradox of landscape is that it is both what is other to the human subject: land, place, nature, and yet, it is also the space for projection, and can become therefore, a sublimated self-portrait.

The artist is interested in the quality of the removed distance which post memory allows and the ways in which memory can be understood as cultural as well as individual. This also gives a context for the layered effect of displacement and distance in the work created through using slides, TV screens and re-filming. The refilmed images are of already mediated images of place-a double distance.

The artist considers that the way in which the results of re-filming distorts and changes might be linked to what happens when she paints. Painting is created through applying layer upon layer onto a surface. The layering in these video stills is not a literal one, but it is another kind of layering has occurred through accumulated processes involved.

Since this sequence of projected images in Hold is so painterly they might be read in counterpoint to some contemporary painting, for example, the filmic, ethereal paintings of Peter Doig. He too privileges neither abstraction nor figuration. He too offers us composite places for projection that draw on as wide a range of source material as Anne Robinson. I am thinking, in this context, not only of the ambiguous almost dream-like sense of space he creates through the rich consistency of his densely worked surfaces, but in particular of his mix of autobiographical and filmic memories.

The use of the fragment brings to mind Victor Burgin’s thoughts on bringing together aspects from different sources:

Enigmatically incomplete fragmentary images –from the real world, from media images, from memory and fantasy- may be woven into delusional constructions of convincing realism.

Enigmatically incomplete fragmentary images –from the real world, from media images, from memory and fantasy- may be woven into delusional constructions of convincing realism.

Susan Hiller, Broodthaers, 2004

Susan Hiller, Broodthaers, 2004

The answer might lie in the notion of haptic visuality. Writing in relation to Susan Hiller, another artist who moves between painting and video, Rosemary Betterton considers that Hiller does not use video as a transparent medium, but in a way that evokes a physical and emotional response more akin to haptic art forms such as painting and sculpture.

Rosemary Betterton draws on remarks Keith Piper made at a seminar:

...the question of artistic subjectivity lies in the creation of a place ‘in between’. As Keith Piper has suggested, this means occupying a space where the artist can make

work that both comes out of his or her particularity and can be read by others within their different social subject-ivities and cultural locations.

Arnold van Gennep’s notion of liminality is as a place of transformation, of transition, which might be considered a place ‘in between’.

...the question of artistic subjectivity lies in the creation of a place ‘in between’. As Keith Piper has suggested, this means occupying a space where the artist can make

work that both comes out of his or her particularity and can be read by others within their different social subject-ivities and cultural locations.

Arnold van Gennep’s notion of liminality is as a place of transformation, of transition, which might be considered a place ‘in between’.

|

See pdf for full text:

|

| ||||||

Slivers of Crystal: Living in the Oscillation by Anne Robinson

Notes from The Afterlife of Memory: Memoria/Historia/Amnesia:

"The film we saw is never the one that I remember.." -Burgin

Edmund Wilson's conception of memory:

"..the brain is an enchanted loom where millions of flashing shuttles weave a

dissolving pattern. the mind recreates reality from the abstractions of sense

impressions.. runs imagined and remembered events back and forth through

time"

How can various forms of re-filming moving images, and the languages of

moving image technologies, including slow motion work in relation to time,

subjectivity and memory, in making and viewing work?

What is the emotional affect of encountering moving image fragments side by

side with painterly freeze frames?

What are the possibilities of the space between frames in digital video as an

imaginative space for artist and spectator? Exploring the space between the

frames of digital video as an imaginary space - alternately a space of reverie,

clarity, rest, pain, rupture or rapture...how can we begin to conceptualize such a

space?

I would like to consider the space between frames as a space of memory, and

the imaginary, a space to be used in making art.

I am also reminded of Bergson's idea of durée, and of memory never really

being lost, only stored, so that yesterday's time and even yesterday's

consciousness continue in current time. This is also relevant to making or looking

at art where time operates in an entirely subjective fashion, expanding or

contracting depending on how much attention is brought to a particular moment -

Notes from The Afterlife of Memory: Memoria/Historia/Amnesia:

"The film we saw is never the one that I remember.." -Burgin

Edmund Wilson's conception of memory:

"..the brain is an enchanted loom where millions of flashing shuttles weave a

dissolving pattern. the mind recreates reality from the abstractions of sense

impressions.. runs imagined and remembered events back and forth through

time"

How can various forms of re-filming moving images, and the languages of

moving image technologies, including slow motion work in relation to time,

subjectivity and memory, in making and viewing work?

What is the emotional affect of encountering moving image fragments side by

side with painterly freeze frames?

What are the possibilities of the space between frames in digital video as an

imaginative space for artist and spectator? Exploring the space between the

frames of digital video as an imaginary space - alternately a space of reverie,

clarity, rest, pain, rupture or rapture...how can we begin to conceptualize such a

space?

I would like to consider the space between frames as a space of memory, and

the imaginary, a space to be used in making art.

I am also reminded of Bergson's idea of durée, and of memory never really

being lost, only stored, so that yesterday's time and even yesterday's

consciousness continue in current time. This is also relevant to making or looking

at art where time operates in an entirely subjective fashion, expanding or

contracting depending on how much attention is brought to a particular moment -

|

See pdf for full text:

|

| ||||||

Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories

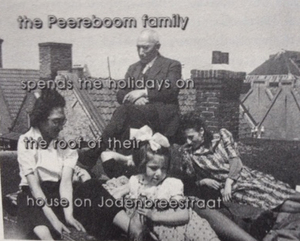

Film still from Peter Forgacs, 1997 movie, The Maelstrom: A Family Chronicle.

Notes from the Introduction of The Home Movie Movement, Excavations, Artifacts, Minings by Patricia R. Zimmerman:

Why Home Movies?

Pg1 Amateur film provides a vital access point for academic historiography in its trajectory from official history to the move variegated and multiple practices of popular memory, a concretization of memory into artifacts that can be remobilized, recontextualized, and reanimated.

Amateur Film and the Project of Film History

In the essay “Wittegenstein Tractatus,” Forgacs proposes that home movies permit us to see the unseen to deconstruct and then reconstruct the human through the ephemeral and microhistorical, where the real and the performed exist side by side. Pg 2

Stories from the Listeners

…all examples incomplete fragments marking the practices and discourses of everyday lived relations that reject grand narratives for micohistorical analysis. Pg 3

…amateur film can be seen as a necessary and vital part of visual culture rather than as a marginal area requiring inclusion. Pg 7

Guha suggests that history requires regrounding in the specifics of everyday life through a creative engagement with the human condition: “No continent, no culture, no mark or condition of social being would be considered too small or too simple for its prose.” Pg7

Guha advocates for an opening up of all the pasts, not simply one, to retrieve retellings, reperceptions, and remakings of our narratives, which are always, and ultimately, acts of invention of possible futures.

In Guha’s terms home movies are stories from the listeners, not the storytellers. It is not that home movies are new, but that our historiographic vision of them is new,, a vision that considers these works by the listeners grounded in the everyday a important and valuable. Pg 8

Rather than analyzing inert artifacts, our project proposes a collective action of digging up, exhuming, mining, excavating, and recontextualizing that which has been buried and lost—amateur films and home movies.

The New Amateur Film Movement

According to most archivists and historians, approximately 50 percent of all Hollywood features before 1951 shot on nitrate are now lost. It is estimated that 80 to 90 percent of all silent films are lost. Pg 9

The Endless and Open Archive of Home Movies

As visual representations, they comprise a distinctive intimate authorship that graphs the depths and complexities of collective memory. As a means of expressive communication, they are reflex constructions inflected by both deliberate and unconscious social, political, and psychic dynamics, symptoms of the contradictions between everyday and popular culture. Pg 19

The archive, then, is not simple a depository, which implies stasis, but is, rather, a retrieval machine defined by its revision, expansion, addition, and change. Jacques Derrida, in his book, Archive Fever, has stated, “The archivist produces more archive. The archive is never closed. It opens out of the future.”

The archive functions as the custodian of collective memories laced with contradictions and ambiguities. It is marked by and inscribed into power relations: who has the power to keep records of the past?

Toward Historical Collage

In history, the process of explaining an event by collecting what seem to be isolated facts under a general hypothesis is called colligation. In the arts, the connection of different kinds of materials and forms to create collisions that in turn generate new ideas is called collage. Montage, the cinematic form of collage, has a long history in cinema as well, derived from the theories of Dziga Vertov and Sergie Eisenstein, who advocated for different ideas operating in collision to create new synthesis and conceptual ideas. Pg 23

Yet, overarching these academic concerns, these essays remind us that the images we recover are always acts of mourning for those who have passed, markers of loss and trauma. It is our responsibility to name these ghosts and make them real through materialization. And it is our responsibility to remember, not with nostalgia for that which is lost, but with hoe that the materiality for these images can be restored and opened to the future through a reconnection with history and others. Pg 24

From the essay Wittgenstein Tractatus: Personal Reflections on Home Movies

By Peter Forgacs

The home movie or private film, not unlike the letter and diary, is biographical. It is one of the most adequate means of remembrance. It is a meditation on “Who am I?” The original context of the private film is the home screening rite, the celebration of times past, or recollection, and of hints of the nonverbal realm of communication and symbols. It is a recollection of the desired intimate vision and aims to immortalize the face of a lover, son, or father or to capture ephemeral moment, landscapes, and rites. The meditation inspired by these screenings is: What has been revealed by making visible that which had remained imperceptible before? Pg. 49

Perhaps the home movie maker, the “hero” of this essay, lies somewhere between the citizen and the voyeur. Pg 51

The “real” and the “performed” act is twofold in the home movie. Our many different roles exemplify the separation and interrelation of our public and private lives. The act of mimesis seems to signify “I exist” or, rather, “I represent myself here for immortality.” This imitation of ourselves is an authentic “copy” of the original, since actor and role are identical. Pg 52

What we later evaluate as a film statement is only a reflection in the moment of filming. And as an intervention it has an influence on the event. The presence of the camera can be sensed, which affect the home movie actors’ behavior. Pushing the button of the camera is an immediate reflection on the present situation. The world “happens” and we record a bit of it. Pg 54

From the essay Ordinary Film: Peter Forgac’s The Maelstrom by Michael S. Roth

But how can home movies of other people hold any interest for us? How can we feel their pull? Pg 63

Artist, theorists, philosophers often flee ordinariness or, as some like to say, try to make the ordinary extraordinary.” I prefer Stanley Cavell’s project, which eh has called, after Wittgenstein, Emerson, and Thoreau, a “quest for the ordinary,” the ordinary being that place where “you first encounter yourself.” How are we to think about our lives and about the pictures from them without separating these images from ourselves, from our ordinary world? …The skeptics might ask how we can be sure that our experiences of images have any meaning at all. ..Leaving oneself open to these responses is a key to his project and is necessary for any kind of real thinking. Pg 65

From the essay Deteriorating Memories: Blurring Fact and Fiction in Home Movies in India by Ayisha Abraham

II. Between Stillness and Movement

Home movies exist as fragment. Slices of differentiated reality come to life, frequently without a beginning or end. The projector plays a vital role in the reclamation process. Without projection, all this film footage is inanimate, a mass of junk lacking any value. Home movies function more as fossils than as discrete images. As a series of stills pass through the gates of a movie projector, this fossilized footage is transformed into movement and memory…. Once the projector switches off and the darkness lifts, amateur films return to their dormant, worthless status. Their history invisible to the naked eye. A delicate balance is produced between stillness and movement, not only in the way that the film in the can becomes “still life” but also in the way that the stills are literally animated to produce the cinematic effect. Pg170

IV. Projecting Light

The projection of reels through light summons a reemergence of the past. The process functions as an Aladdin’s lamp, offering wishes, dreams, and unknown images. This phenomenological and physical experience of projected light distinguishes the home movie from the photograph, which might deteriorate but is nonetheless continuously visible. Pg 172

Ishizuka , K. L., & Zimmerman, P. R. (2008). Mining the home movie: Excavations in histories and memories. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Why Home Movies?

Pg1 Amateur film provides a vital access point for academic historiography in its trajectory from official history to the move variegated and multiple practices of popular memory, a concretization of memory into artifacts that can be remobilized, recontextualized, and reanimated.

Amateur Film and the Project of Film History

In the essay “Wittegenstein Tractatus,” Forgacs proposes that home movies permit us to see the unseen to deconstruct and then reconstruct the human through the ephemeral and microhistorical, where the real and the performed exist side by side. Pg 2

Stories from the Listeners

…all examples incomplete fragments marking the practices and discourses of everyday lived relations that reject grand narratives for micohistorical analysis. Pg 3

…amateur film can be seen as a necessary and vital part of visual culture rather than as a marginal area requiring inclusion. Pg 7

Guha suggests that history requires regrounding in the specifics of everyday life through a creative engagement with the human condition: “No continent, no culture, no mark or condition of social being would be considered too small or too simple for its prose.” Pg7

Guha advocates for an opening up of all the pasts, not simply one, to retrieve retellings, reperceptions, and remakings of our narratives, which are always, and ultimately, acts of invention of possible futures.

In Guha’s terms home movies are stories from the listeners, not the storytellers. It is not that home movies are new, but that our historiographic vision of them is new,, a vision that considers these works by the listeners grounded in the everyday a important and valuable. Pg 8

Rather than analyzing inert artifacts, our project proposes a collective action of digging up, exhuming, mining, excavating, and recontextualizing that which has been buried and lost—amateur films and home movies.

The New Amateur Film Movement

According to most archivists and historians, approximately 50 percent of all Hollywood features before 1951 shot on nitrate are now lost. It is estimated that 80 to 90 percent of all silent films are lost. Pg 9

The Endless and Open Archive of Home Movies

As visual representations, they comprise a distinctive intimate authorship that graphs the depths and complexities of collective memory. As a means of expressive communication, they are reflex constructions inflected by both deliberate and unconscious social, political, and psychic dynamics, symptoms of the contradictions between everyday and popular culture. Pg 19

The archive, then, is not simple a depository, which implies stasis, but is, rather, a retrieval machine defined by its revision, expansion, addition, and change. Jacques Derrida, in his book, Archive Fever, has stated, “The archivist produces more archive. The archive is never closed. It opens out of the future.”

The archive functions as the custodian of collective memories laced with contradictions and ambiguities. It is marked by and inscribed into power relations: who has the power to keep records of the past?

Toward Historical Collage

In history, the process of explaining an event by collecting what seem to be isolated facts under a general hypothesis is called colligation. In the arts, the connection of different kinds of materials and forms to create collisions that in turn generate new ideas is called collage. Montage, the cinematic form of collage, has a long history in cinema as well, derived from the theories of Dziga Vertov and Sergie Eisenstein, who advocated for different ideas operating in collision to create new synthesis and conceptual ideas. Pg 23

Yet, overarching these academic concerns, these essays remind us that the images we recover are always acts of mourning for those who have passed, markers of loss and trauma. It is our responsibility to name these ghosts and make them real through materialization. And it is our responsibility to remember, not with nostalgia for that which is lost, but with hoe that the materiality for these images can be restored and opened to the future through a reconnection with history and others. Pg 24

From the essay Wittgenstein Tractatus: Personal Reflections on Home Movies

By Peter Forgacs

The home movie or private film, not unlike the letter and diary, is biographical. It is one of the most adequate means of remembrance. It is a meditation on “Who am I?” The original context of the private film is the home screening rite, the celebration of times past, or recollection, and of hints of the nonverbal realm of communication and symbols. It is a recollection of the desired intimate vision and aims to immortalize the face of a lover, son, or father or to capture ephemeral moment, landscapes, and rites. The meditation inspired by these screenings is: What has been revealed by making visible that which had remained imperceptible before? Pg. 49

Perhaps the home movie maker, the “hero” of this essay, lies somewhere between the citizen and the voyeur. Pg 51

The “real” and the “performed” act is twofold in the home movie. Our many different roles exemplify the separation and interrelation of our public and private lives. The act of mimesis seems to signify “I exist” or, rather, “I represent myself here for immortality.” This imitation of ourselves is an authentic “copy” of the original, since actor and role are identical. Pg 52

What we later evaluate as a film statement is only a reflection in the moment of filming. And as an intervention it has an influence on the event. The presence of the camera can be sensed, which affect the home movie actors’ behavior. Pushing the button of the camera is an immediate reflection on the present situation. The world “happens” and we record a bit of it. Pg 54

From the essay Ordinary Film: Peter Forgac’s The Maelstrom by Michael S. Roth

But how can home movies of other people hold any interest for us? How can we feel their pull? Pg 63

Artist, theorists, philosophers often flee ordinariness or, as some like to say, try to make the ordinary extraordinary.” I prefer Stanley Cavell’s project, which eh has called, after Wittgenstein, Emerson, and Thoreau, a “quest for the ordinary,” the ordinary being that place where “you first encounter yourself.” How are we to think about our lives and about the pictures from them without separating these images from ourselves, from our ordinary world? …The skeptics might ask how we can be sure that our experiences of images have any meaning at all. ..Leaving oneself open to these responses is a key to his project and is necessary for any kind of real thinking. Pg 65

From the essay Deteriorating Memories: Blurring Fact and Fiction in Home Movies in India by Ayisha Abraham

II. Between Stillness and Movement

Home movies exist as fragment. Slices of differentiated reality come to life, frequently without a beginning or end. The projector plays a vital role in the reclamation process. Without projection, all this film footage is inanimate, a mass of junk lacking any value. Home movies function more as fossils than as discrete images. As a series of stills pass through the gates of a movie projector, this fossilized footage is transformed into movement and memory…. Once the projector switches off and the darkness lifts, amateur films return to their dormant, worthless status. Their history invisible to the naked eye. A delicate balance is produced between stillness and movement, not only in the way that the film in the can becomes “still life” but also in the way that the stills are literally animated to produce the cinematic effect. Pg170

IV. Projecting Light

The projection of reels through light summons a reemergence of the past. The process functions as an Aladdin’s lamp, offering wishes, dreams, and unknown images. This phenomenological and physical experience of projected light distinguishes the home movie from the photograph, which might deteriorate but is nonetheless continuously visible. Pg 172

Ishizuka , K. L., & Zimmerman, P. R. (2008). Mining the home movie: Excavations in histories and memories. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.